How Imitation Really Works and When Waiting Makes Economic Sense

Every few years, a consumer product enters the market at a price that feels excessive yet defensible. The cost appears inflated, but the experience is meaningfully different. Early adopters pay. Others wait, assuming cheaper alternatives will soon appear. In most cases, they do. The question is not whether this pattern repeats but why it unfolds so predictably and over what timescale.

This article examines that pattern through an economic lens. The Dyson Airwrap serves as a concrete example, not because it is exceptional but because it illustrates a broader process that governs how complex consumer technologies move from novelty to normality.

Breakthroughs Are Systems, Not Isolated Inventions

What consumers label as "new technology" is rarely a single invention. It is almost always a system. Known components are integrated in a way that reduces friction across multiple dimensions of use.

Hardware, software, materials, ergonomics, safety constraints, and manufacturing tolerances are aligned to deliver a consistent experience. From an economic perspective, this integration is the innovation. Individual components can be copied quickly. System coherence cannot.

Early imitations often reproduce the visible form of a product while failing to match performance across conditions. They may function in principle but break down in practice through noise, heat, inconsistency, or durability issues. The gap is not aesthetic. It is structural.The first firm to solve these constraints captures value not through exclusivity of parts but through exclusivity of reliable performance.

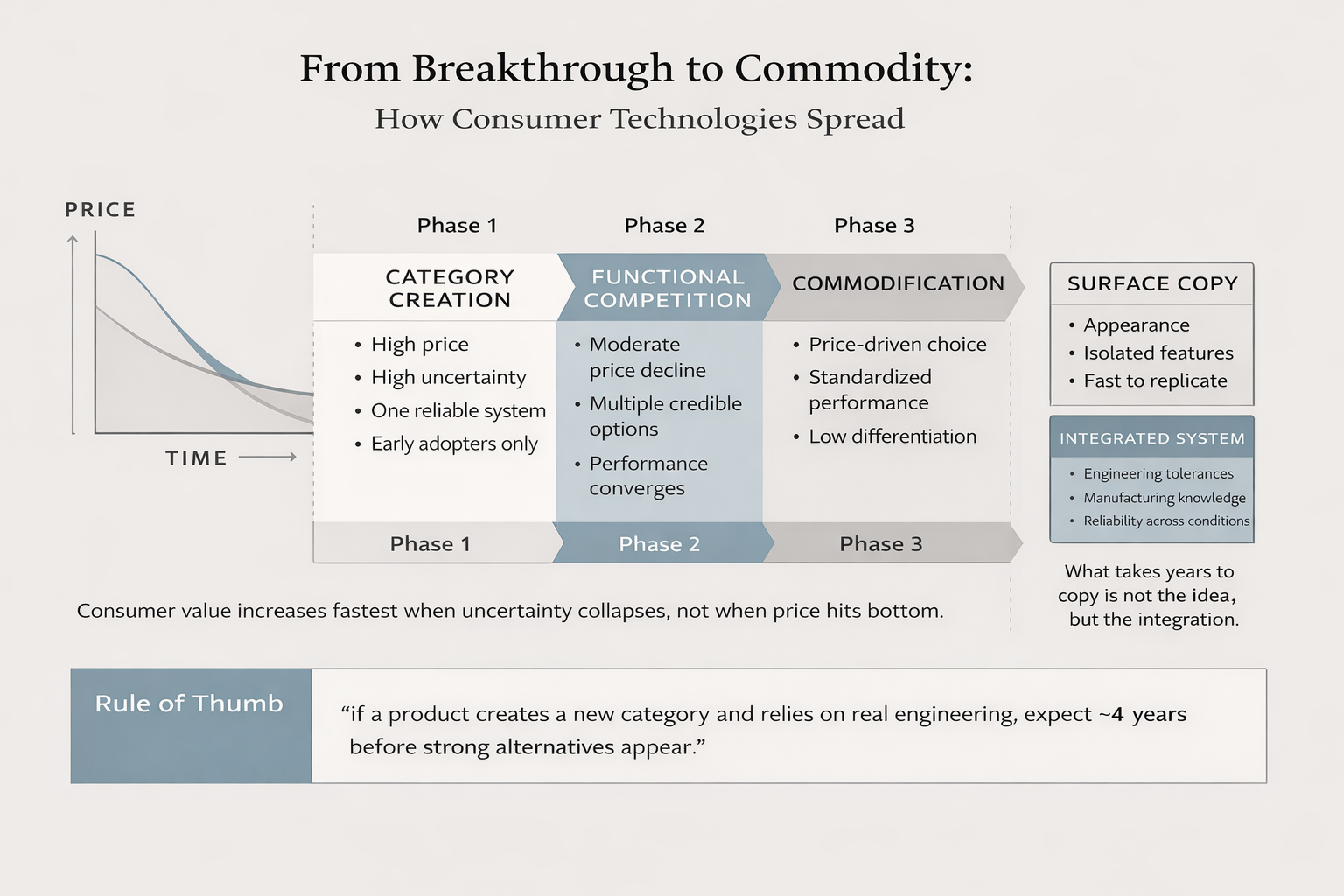

Most successful consumer technologies follow a three-phase trajectory.

Phase one is category creation. A firm defines a new way of performing a task. Prices are high, margins are strong, and early adopters accept the premium because no functional alternatives exist.

Phase two is functional competition. Other firms enter with products that approximate the original outcome through different technical pathways. Prices begin to fall, but more importantly, uncertainty declines. Consumers gain real choice.

Phase three is commodification. The technology becomes standardized. Performance differences narrow for most users. Price becomes the primary differentiator.

For consumers, the economically relevant shift occurs in phase two, not phase three. That is when waiting ceases to generate meaningful additional value.

The delay between innovation and credible competition is not accidental.

Engineering constraints matter. Products involving heat, airflow, pressure, or close bodily interaction require extended testing. Failures here are costly and visible.

Intellectual property imposes friction. Patents rarely prevent entry entirely but slow direct copying and force competitors to invest in alternative designs.

Manufacturing knowledge matures gradually. Early in a category's life, suppliers lack experience. Over time, yields improve, tolerances tighten, and costs fall without sacrificing quality.

Trust accumulates slowly. Consumers require evidence of reliability across time, use cases, and failure modes. Markets price this uncertainty. These factors explain why effective substitutes tend to appear years later, not months.

The Airwrap as a Typical Case

The Dyson Airwrap did not invent airflow or hair styling. It integrated controlled airflow, temperature management, and modular design into a system that reduced heat damage while producing predictable results.

For several years, alternatives existed primarily as visual analogues. Roughly four years later, credible competitors emerged. At that point, consumers were no longer choosing between an original and compromised copies but between competing interpretations of the same category.

This timeline is typical for complex consumer hardware.

What Consumers Are Actually Optimizing

Consumers are not simply comparing prices. They are managing uncertainty.

They balance frequency of use against expected future price reductions. They assess the risk of double spending after disappointment. They evaluate friction, learning curves, and reliability. They consider longevity, repairability, and resale value.

The decision is not expensive versus cheap. It is certainty now versus uncertainty later.

When Waiting Is Rational

Waiting makes economic sense when a category is young and uncertainty remains high. It also makes sense when usage is infrequent or existing tools already meet most needs. In these cases, early adoption primarily purchases novelty.

When Buying Early Is Rational

Buying early is rational when a product reliably solves a recurring problem and reduces friction over time. If it replaces multiple tools, saves time weekly, or prevents damage, the premium can amortize quickly.

The error is not early adoption. The error is assuming that waiting always improves value.

A Practical Rule

If a product creates a new category and depends on real engineering, expect roughly four years before strong alternatives appear.

Before that, cheaper options are usually compromised. After that, good enough becomes widespread.

Conclusion

Technologies become ordinary not when they are copied but when they are understood, manufactured reliably, and trusted.

The first generation proves possibility. The second proves viability. The third proves affordability. High prices are not market failures. They are signals. They indicate where uncertainty still exists and how long it may take before value diffuses.

The Dyson Airwrap is not an exception. It is a visible instance of a quiet, repeatable economic process.

Suggested reading and sources

For readers who want to go deeper, several works provide useful context.

Clayton Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma explains how new categories emerge and why incumbents often fail to respond effectively.

Brian Arthur’s The Nature of Technology explores technology as evolving systems rather than isolated inventions. W. Brian Arthur and Paul David’s work on path dependence helps explain why early design choices shape long-term markets. On uncertainty and adoption, Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations remains foundational. For a modern perspective on hardware, manufacturing, and scale, The Power Law by Sebas