Lord of the Flies by William Golding

The horror of watching innocence disappear. Lord of the Flies is often described as a novel about civilization versus savagery, but that framing always feels too abstract to me. What made the book genuinely difficult to read was not the violence itself, but the slow, irreversible loss of innocence among the children. The horror lies in how ordinary that loss becomes.

Warning:

This article discusses a novel containing violence, murder of children, bullying, and the psychological breakdown of minors in isolation.

What it is about

I first read this in school, like most people. I read it again last year and found it worse the second time. Not because the book had changed, but because I understood more clearly what I was watching happen.

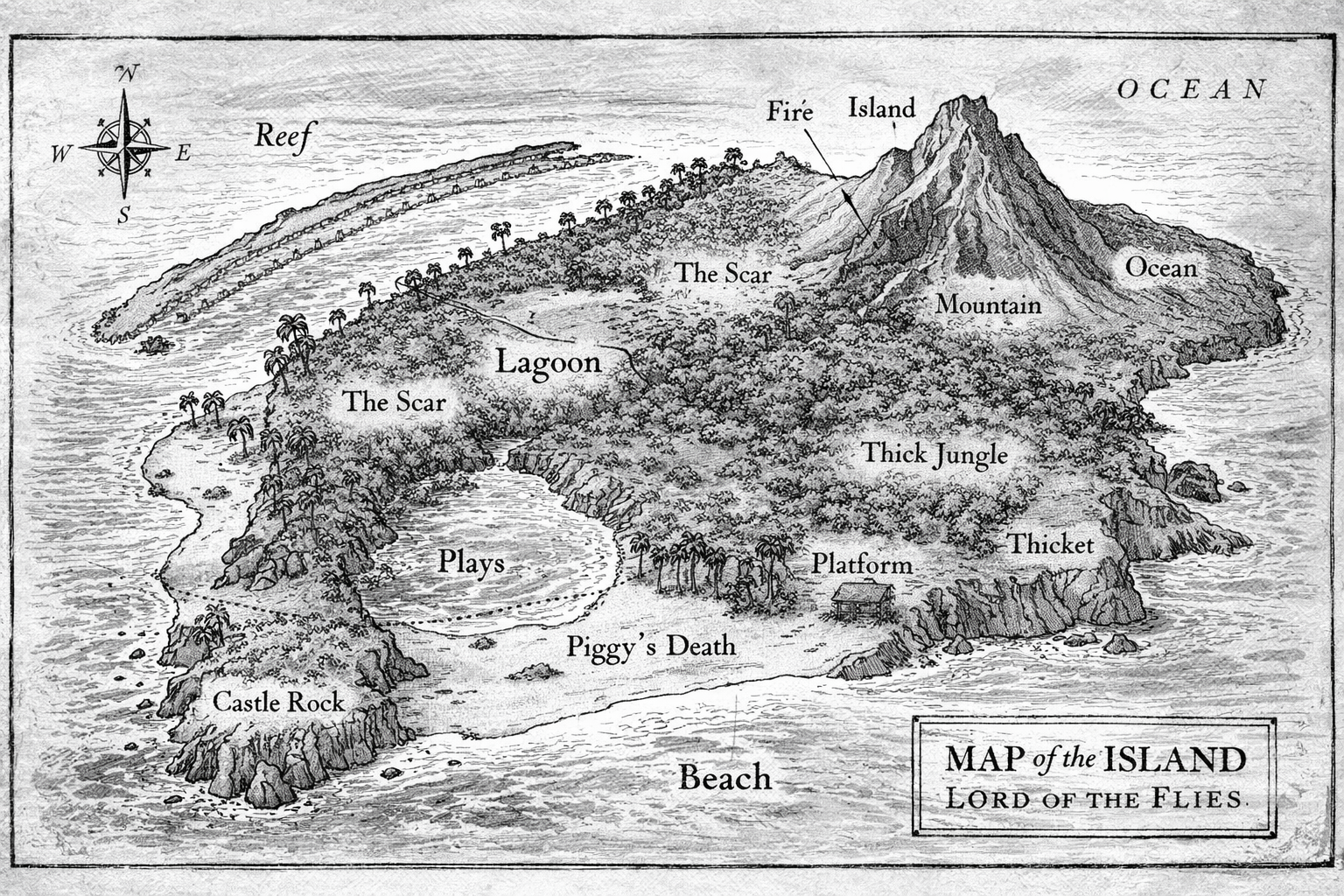

A group of schoolboys survives a plane crash and ends up stranded on a deserted island without adult supervision. At first, they attempt to recreate order through rules, assemblies, and shared responsibility. Gradually, fear, power struggles, and the desire to belong erode those structures, leading the group toward brutality.

The plot is deceptively simple. What gives it weight is the precision with which Golding tracks the disintegration. Each small compromise, each rationalization, each moment where cruelty is justified as necessity or play.

What stayed with me

The most disturbing aspect is not that the boys become violent, but how naturally it happens. Games turn into rituals. Authority turns into dominance. What begins as play slowly sheds its innocence until it is no longer play at all. Reading it, I felt a persistent sense of mourning for something being lost rather than shock at what was gained.

The children do not suddenly become monsters. They remain recognizably children even as they do unforgivable things. That is what makes the novel unsettling. Their cruelty is tangled with fear, excitement, and the need for acceptance. The line between childhood and savagery erodes quietly, almost politely.

Piggy’s glasses become a weapon. The conch becomes meaningless. Simon’s gentleness becomes a liability. Each symbol of civilization is stripped of function until what remains is purely ritualistic violence disguised as order.

Why it is difficult

The book forces you to sit with the idea that innocence is not protected by age. Watching children abandon empathy, reason, and care for one another creates a specific kind of grief. There is no comforting adult perspective to intervene, no moral voice to reassure you that this is an exception. The absence of guidance is total.

What makes it harder is that Golding does not frame the boys as inherently evil. They are not damaged or exceptional. They are ordinary children placed in circumstances that strip away the social structures that normally constrain behavior. The implication is clear and bleak: this could happen to anyone.

There is a scene in chapter four where the boys hunt a pig. Jack, Roger, and the others circle it, chanting "Kill the pig. Cut her throat. Spill her blood." They drive it toward panic. Maurice mimics the pig's squealing. The others laugh. Golding presents it as rough play, violent but contained within the frame of hunting for food.

Then it happens again in chapter seven. The same chant. The same circling. But this time Robert plays the pig in a mock hunt. The boys grab him, jab him with spears, chant louder. Robert screams that they are hurting him. They do not stop. Ralph himself feels "the desire to squeeze and hurt" and is "thick with lust." The boys do not wake up one morning and decide to become killers. They rehearse it. Jack declares the beast must be hunted. Roger learns that throwing rocks near the littluns brings no consequences, then throws them closer. The older boys paint their faces and claim it is for camouflage, then discover it lets them act without shame. By the time Roger levers the boulder that kills Piggy, the progression is complete. He has practiced smaller cruelties until this one felt inevitable.

Golding does not give you distance. You watch it happen in real time. You see Ralph hesitate when Jack challenges him, then yield to avoid conflict. You see Piggy warn that the signal fire is going out while the hunters abandon it for a kill. You see the moments where intervention could have mattered, and you see those moments pass.

The tragedy is not that the boys are stranded on an island. The tragedy is that no one stops them from becoming what they become, and by the end, no one wants to.

When the naval officer arrives in chapter twelve and treats the whole thing as "a pack of British boys" playing at savages, it is almost unbearable. He sees painted faces and makeshift spears and assumes games. The reader knows Simon was murdered during a ritual dance. The reader knows Piggy was killed deliberately, his body swept out to sea while his glasses—the last tool of civilization—remained in Jack's possession. The reader knows Ralph spent the final chapter being hunted like the pigs before him.

That final image—Ralph weeping for "the end of innocence, the darkness of man's heart"—is not catharsis. It is acknowledgment. The innocence is gone. It is not coming back. And the naval officer, arriving from a ship engaged in its own war, has no idea what he is rescuing the boys from. Or that he represents the same violence, just organized under flags and ranks instead of painted faces and chants.

Style and tone

Golding’s prose is deceptively simple. The island is described with clarity and beauty, which makes the violence feel even more jarring. The contrast between lush nature and human collapse reinforces the idea that the danger is not the environment, but what the boys bring with them.

The structure is linear and relentless. There is no subplot, no digression, no relief. The novel moves in one direction: toward disintegration. That singularity of focus is part of what makes it so effective and so exhausting.

Themes and cultural resonance

Lord of the Flies interrogates the myth of childhood innocence and the assumption that civilization is our natural state. It suggests instead that social order is fragile, maintained through constant effort and easily abandoned when fear takes over.

The novel also explores how power operates in the absence of accountability. Jack does not seize power through force alone. He offers belonging, excitement, and the promise of safety through violence. The boys follow him not because they are coerced, but because what he offers feels more immediate than what Ralph represents.

This is why the book remains relevant. It is not about children on an island. It is about how groups function when fear replaces reason, and how quickly the mechanisms of exclusion and scapegoating take hold.

Verdict

Lord of the Flies was not an immediate success when it was published in 1954, but it became a staple of school curriculums and has remained in print ever since. It is frequently taught as an allegory about human nature, though scholars debate whether Golding’s pessimism is justified or overstated.

Some readers find it too bleak. Others argue that its bleakness is the point. The novel does not offer hope, but it does offer clarity about what happens when social bonds break down.

There is also the absence of girls, which limits the scope of what the book can say about human nature. Golding frames this as a story about boys specifically, but the universalizing language he uses suggests he sees it as broader commentary. That tension is never resolved.

Lord of the Flies endures because it does not offer distance. It asks the reader to witness the erosion of innocence in real time, and to recognize how fragile civility is when fear replaces care. What makes it painful is not what the children do, but that they were once capable of something gentler, and that gentleness does not survive. The book does not argue that we are doomed. It argues that we are responsible. And that without vigilance, the structures that protect us from ourselves will not hold.

Similar books

The Girls by Emma Cline. A different kind of group disintegration, but the same mechanics of belonging, fear, and the slow normalization of harm.

We Need to Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver. For the way it refuses to locate evil in clear causes and instead examines how violence emerges from ordinary circumstances.

The Road by Cormac McCarthy. Another story about the collapse of civilization, though focused on a father trying to preserve morality rather than children abandoning it.