Dadaism

Kim Traynor, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

When Reason Failed: Dadaism

The Birth of Anti-Art

In February 1916, at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, Switzerland, a new kind of art was born. Hugo Ball recited sound poetry while wearing a cardboard costume shaped like an obelisk. Emmy Hennings sang satirical songs. Richard Huelsenbeck beat drums and shouted simultaneous poems. Marcel Janco's abstract masks hung on the walls as dancers improvised to noise music. Multiple poets read different texts in different languages at the same time.

This was not performance art as decoration, nor mere cacophony. It was deliberate sensory and categorical overload, designed to make traditional art criticism impossible. The artists argued that if modern society and logic had led to the mechanized slaughter of World War I, then logic and traditional art should be rejected entirely. If reason had produced industrial-scale death, then perhaps reason itself deserved no respect. Nonsense became a form of resistance. Chaos became clarity.

What followed was not a style but an attitude, a movement that questioned authorship, originality, and cultural authority long before these became academic debates. Dadaism was an anti-art movement, a philosophical stance disguised as performance, a refusal disguised as creativity. It questioned everything previous generations had taken for granted about what art was, who could make it, and what it was for. Most radically, Dada refused to stay within the boundaries of any single art form. Poetry became visual. Visual art became performance. Performance became poetry. The deliberate confusion was the point.

To understand Dadaism is to understand what happens when an entire generation loses faith in the systems that raised it.

More Than Words: The Intermedial Nature of Dada

The fundamental misunderstanding about Dadaism is that it was primarily a literary movement. It was not. Dada was radically intermedial from its inception, deliberately refusing to stay within established art forms.

Hannah Höch cut up photographs from mass media and reassembled them into impossible bodies and political critiques. Her masterwork "Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany" sliced politicians, dancers, machinery, and text into chaotic composition. The seams were visible because the artificiality was the point.

Kurt Schwitters collected bus tickets, cigarette packaging, newspaper fragments, wood scraps, and fabric, then assembled them into layered compositions. His "Merzbau" was an evolving architecture-sculpture built inside his house. He elevated discarded materials through aesthetic attention, attacking the hierarchy of worthy materials and the museum's preference for expensive media.

Raoul Hausmann created poster-poems where his face screams surrounded by letterforms as objects. Typography exploded across the surface without linear reading path. Text and image merged into single artifact, destroying the separation between reading and looking.

Marcel Duchamp submitted a urinal to an art exhibition in 1917, signed "R. Mutt." He drew a moustache on a reproduction of the Mona Lisa. These ready-mades recontextualized existing objects as art through selection and framing, with minimal intervention but maximum conceptual disruption.

Why Intermediality Mattered

Intermediality was not peripheral decoration but central strategy. Dada practiced it for specific reasons.

First, it sabotaged institutional control. Museums, galleries, critics, and markets depended on categorization. A painting went in the painting section and commanded painting prices. By creating works that resisted categorization, Dadaists made filing impossible. Is a photomontage-poem visual art or literature? This categorical confusion was a weapon against bourgeois cultural authority.

Second, it rejected specialization. Bourgeois culture valued the painter who only painted, the poet who only wrote. Dada refused this division of labor. Schwitters made poetry, collage, architecture, and performance. Höch made photomontage, embroidery, and wrote. The Renaissance person model challenged industrial compartmentalization.

Third, sensory overload became philosophical statement. If rationalism had produced World War I, then overwhelming the rational faculties through sensory bombardment might break through to something else. Simultaneous poetry made comprehension impossible, forcing audiences into confusion and presence rather than understanding.

Fourth, it reflected modern experience. Early twentieth-century life already involved intermediality. Newspapers combined text, photographs, and advertisements. Cities assaulted the senses with signs, sounds, crowds. Cinema merged image and music. Dada mirrored this sensory chaos rather than retreating into pure art forms.

Dada in the Low Countries

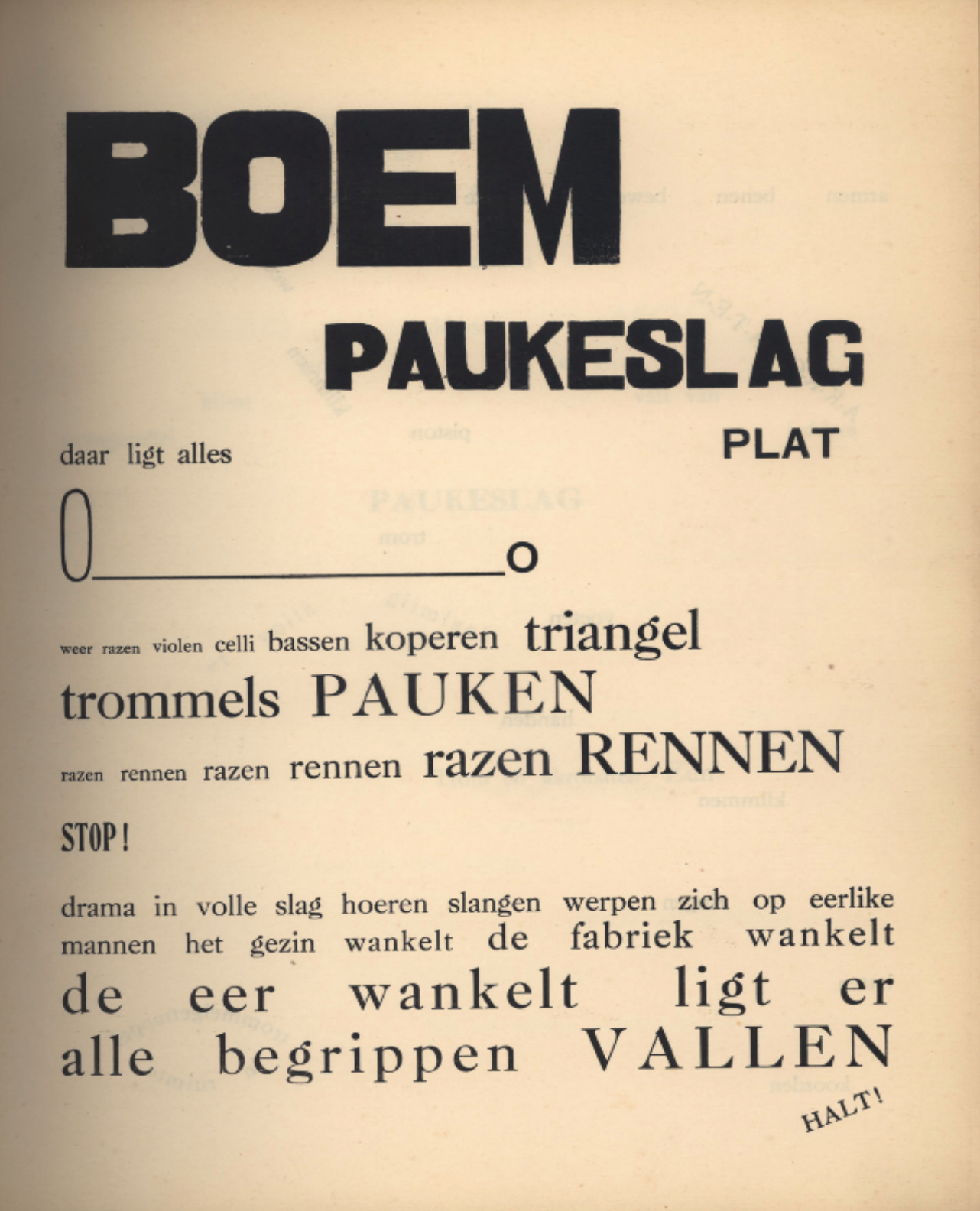

The movement spread beyond Zurich to Berlin, Paris, and New York, eventually reaching the Netherlands and Belgium. Paul van Ostaijen, initially a humanitarian expressionist, became heavily influenced by Dadaism while living in Berlin between 1919 and 1921. His work "Bezette Stad" (Occupied City) and its famous poem "Boem Paukeslag" utilized rhythmic typography where words functioned as visual images or musical scores rather than traditional text. The work has been described as chaos you cannot catch in the blink of an eye.

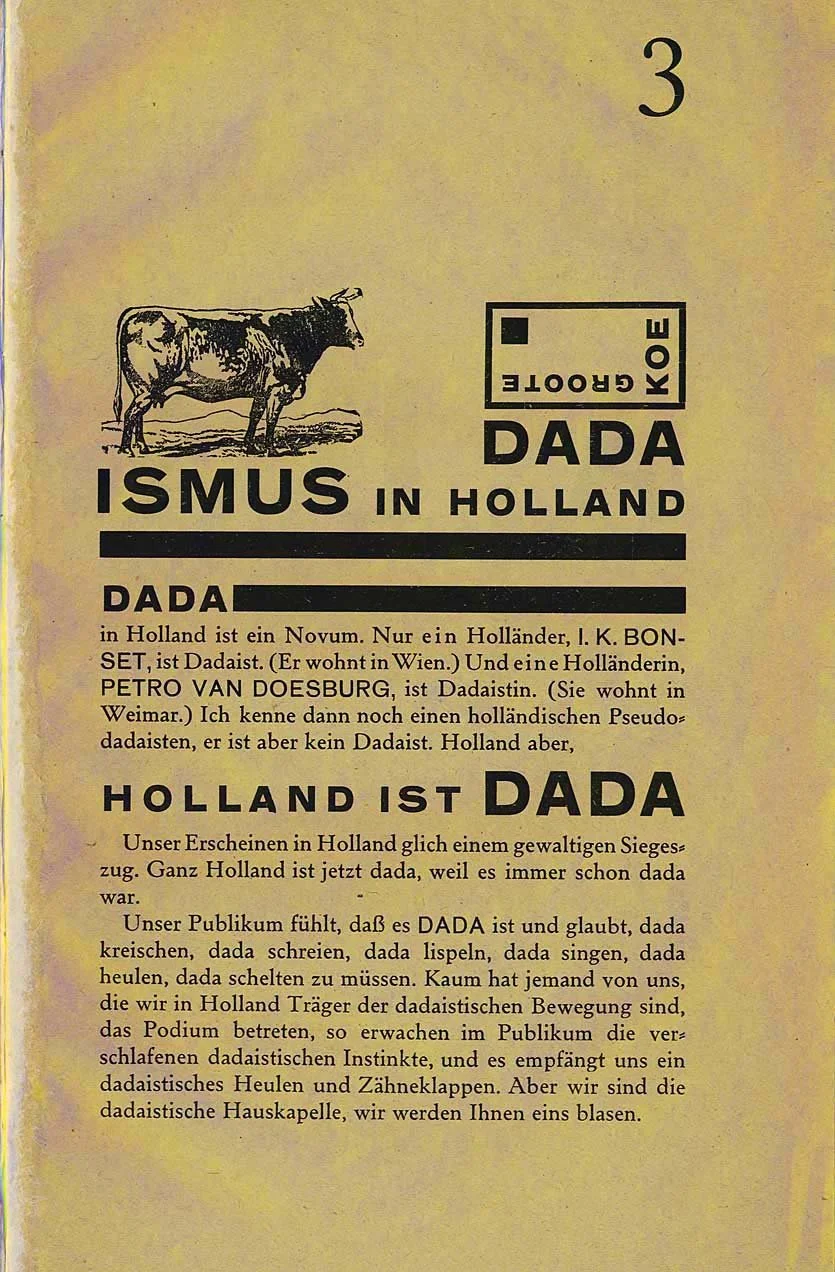

Theo van Doesburg, a Dutch artist central to the structured De Stijl movement, adopted the pseudonym I.K. Bonset to explore Dadaism's chaotic nature. He bridged the gap between geometric order and deliberate disruption, demonstrating how the same artist could operate in contradictory modes.

The significance of these Dutch-language contributions is preserved in the International Dada Archive, where digital scans of "Bezette Stad" remain available for research. Contemporary Dutch theater groups like Fast Forward have translated "Boem Paukeslag" into performance, attempting to capture the screamed and whispered essence of the original typography.

What Dada Destroyed

Dada artists embraced chance, fragmentation, and provocation. Poems were assembled by drawing words from a hat. Artworks mocked seriousness. Performances disrupted audiences rather than pleasing them. Meaning was treated as unstable and often deliberately sabotaged.

The movement destroyed boundaries systematically. Between art forms, collapsing poetry, painting, and performance into single events. Between high and low culture, giving bus tickets the same aesthetic attention as oil paintings. Between artist and audience, making events participatory rather than spectatorial. Between sense and nonsense, using logic to reveal illogic.

What makes Dadaism enduring is not its style but its attitude. By refusing to explain itself, Dada exposed how much art depends on context and expectation. It was not trying to replace one system with another. It was trying to break the idea that systems deserve obedience at all.

The avant-garde moment passed. Dadaism largely transitioned into Surrealism by the mid-1920s. But the questions remain relevant. What happens when reason fails? What do we do when the systems that claim to make sense produce catastrophe? How do we resist when resistance itself can be commodified?

Dadaism suggested one answer. Smash the mirror. Show that the world it reflected was never whole, rational, or beautiful. Create work that cannot be categorized, commodified, or controlled. Make nonsense that reveals the nonsense we pretend is sense.

Kurt Schwitters, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

I tried my hand at this genre and humbly leave my poetry here with the trembling hands of an artist.

Understanding Dada requires recognizing that text and image operated together as meaning-making apparatus. The movement deliberately created works that could not be categorized as painting or poetry alone.

Any contemporary engagement with Dadaism must honor this intermedial spirit. Words on white pages would betray the movement's essence. Screenshot poetry, typographic noise, interface aesthetics, deliberate glitches in smooth systems, these are the contemporary equivalents of Schwitters' bus tickets and Höch's cut-up newspapers.

What makes Dadaism enduring is not its style but its attitude. It questioned authorship, originality, and cultural authority long before these became academic debates. By refusing to explain itself, Dada exposed how much art depends on context and expectation.Dadaism was not trying to replace one system with another. It was trying to break the idea that systems deserve obedience at all.

Not as style. As necessity.

Scan from Van Ostaijen, Paul. Bezette Stad. First publication, De Sikkel, Antwerpen, 1918-1921. Accomplished by Geert Buelens.

Kurt Schwitters, Antony Kok, Theo van Doesburg, Hannah Höch, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons