The Death of Stalin: When Terror Becomes Farce Becomes Funny

The Death of Stalin is often described as a farce about a historical moment. That description undersells its intent. The film is not primarily about the Soviet Union, nor even about Joseph Stalin himself. It is about power once its god disappears and the sudden exposure of the vacuum underneath. The premise is simple. Stalin dies. His inner circle panics.

What follows is not grief but logistics, alliances, betrayals, and frantic repositioning.

It’s Super Funny Because It’s True

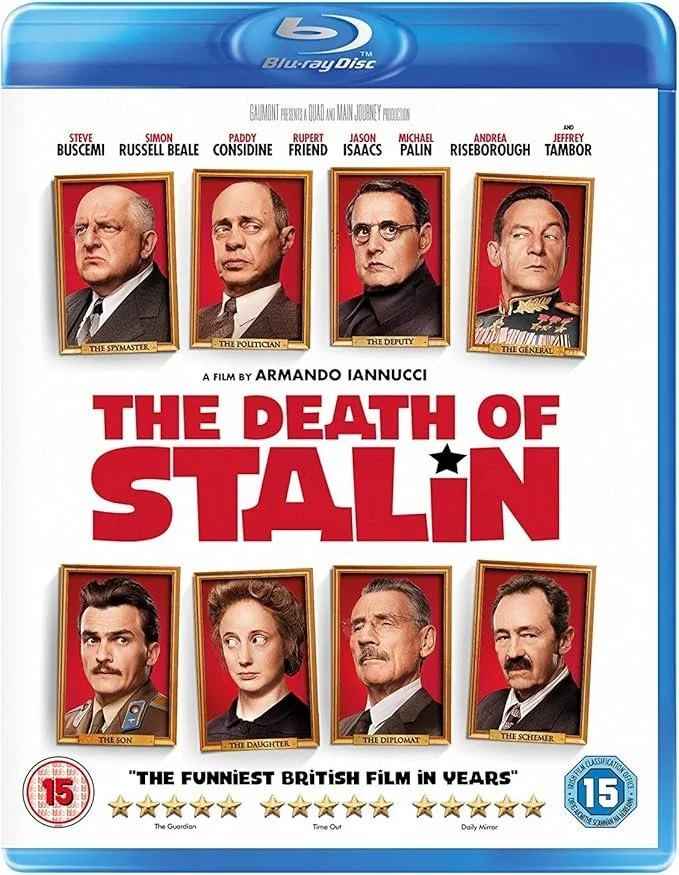

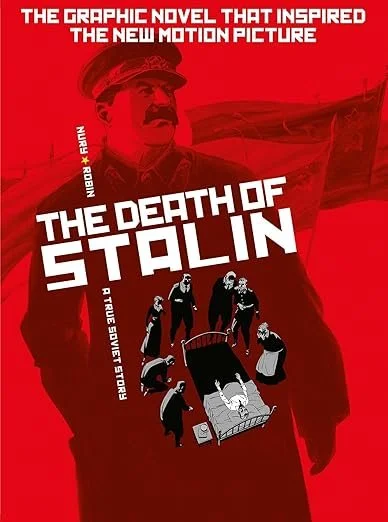

Based on a French graphic novel by Fabien Nury and Thierry Robin, the film turns one of the bloodiest political transitions in modern history into black comedy. Stalin dies in 1953. A brutal scramble for power follows. The material includes mass executions, show trials and systematic terror. On paper, the premise sounds tasteless. In execution, it becomes devastatingly precise.

What makes the absurdity work is restraint and accuracy. Many of the film's most outrageous moments come directly from historical record. Reality required no embellishment. It was already grotesque. The humor emerges from speed and cruelty rather than punchlines, from watching men accustomed to absolute fear suddenly lose its source.

The rapid-fire dialogue is deliberately anachronistic. Characters insult each other in modern language rather than period speech. This isn't carelessness. It's a statement. The behavior isn't uniquely Soviet. Strip away uniforms and slogans and the same dynamics reappear in boardrooms, parliaments and institutions today.

I have to say, the cast of this movie is chef’s kiss and Steve Buscemi is an absolute doll in here.

The Zebra Principle

Beneath the comedy lies sharp political insight. The film demonstrates what you might call the Zebra Principle. In Stalin's Soviet Union, standing out meant death. Survival depended on blending in, never disagreeing, speaking only when consensus was already visible. Ministers learned to perform constant vigilance, joking and flattering to stay in motion.

When Stalin dies, this strategy collapses. The zebras suddenly need to lead. They spent decades following Stalin's reality, agreeing with whatever he declared. Now they must manufacture reality themselves.

The film captures this through small, devastating details. Khrushchev obsessively takes notes after meetings, trying to mirror Stalin's last positions. He burns them once Stalin is gone. The past becomes useless overnight.

A key scene between Beria and Stalin’s daughter Svetlana underscores the film’s understanding of power.

Beria offers comfort and reassurance, presenting himself as protector. Truth enters only when it becomes useful as leverage.

In this world, truth is not moral. It is tactical and the film never suggests otherwise.

The History Buff Fact-Check

Many of the film's most outlandish moments are real. Stalin was found lying in a puddle of his own urine after guards delayed entering his room out of terror. The leadership struggled to find competent doctors because Stalin had recently purged Moscow's best physicians during the paranoid Doctor's Plot of 1952 to 1953.

The Radio Moscow concert incident happened, though not on the night of Stalin's death. In 1944, Stalin demanded a recording of a live performance that hadn't been recorded. This triggered a frantic restaging with a terrified replacement conductor. Pianist Maria Yudina did include a note with the recording, though its exact wording remains disputed.

The family details are accurate too. Vasily Stalin helped cover up a plane crash that killed his air force hockey team. Molotov's wife Polina was arrested and sent to the gulag. Molotov continued serving Stalin dutifully and even voted in favor of her arrest.

Impact and Verdict

Russian authorities banned the film. But The Death of Stalin isn't just about the Soviet Union.

It's an autopsy of how totalitarian systems work. Not through ideology but through fear, conformity and terrified bureaucrats maneuvering for survival. The pattern is universal.

The king is dead. Long live the king.

These weren't giants of history. They were mediocrities stumbling through atrocities, sustained by a system that rewarded obedience and punished hesitation. The mechanisms remain familiar wherever power resists accountability.

The film understands that history already delivered the joke. The goal is demystification.

Power isn't noble or intelligent. It survives through chaos, speed and the fear of being next.