Releasing the Mad: Tony Robert Fleury and the Birth of Modern Psychiatry

Tony Robert-Fleury, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The painting often referred to as The Release of the Mad is more formally known as Pinel Frees the Madwomen at the Salpêtrière.

Painted in 1876 by Tony Robert-Fleury, it depicts a moment that is both historical and symbolic.

A physician stands before a group of restrained women and orders their chains removed.

On the surface, the scene looks humane, almost sentimental. Take a moment to look closer and you might feel that something is wrong.

The man at the center is Philippe Pinel. He was a key figure in mental health reform during the French Revolution.

Pinel argued that people deemed insane shouldn't be treated like criminals or animals. They were patients. Removing chains wasn't just practical. It was a philosophical break with everything that came before.

Robert Fleury paints this rupture using light. Light falls on Pinel and the act of release, while the women remain partially in shadow. Some appear confused. Others stare blankly. A few seem frightened rather than relieved. Freedom here is not triumphant. It's destabilizing.

The way Fleury depicts the scene shows his awareness that this act cuts both ways. He doesn't romanticize madness or celebrate liberation. He captures uncertainty. What happens when you tear down a system of control but have nothing ready to replace it?

This is the most crucial question any liberation movement should ask itself, even when it's uncomfortable. What happens next?

The painting reflects a turning point in an actual debate raging through late eighteenth century France.

Was madness a physical disease of the brain and nerves, or could it stem from psychological and social causes?

The Enlightenment pushed reason and science into every corner of society, and the treatment of the insane became a test case.

Could reason reform what had always been cast out as unreason?

William Cullen, a Scottish physician whose work Pinel translated, classified mental disorders as "neuroses" of the nervous system.

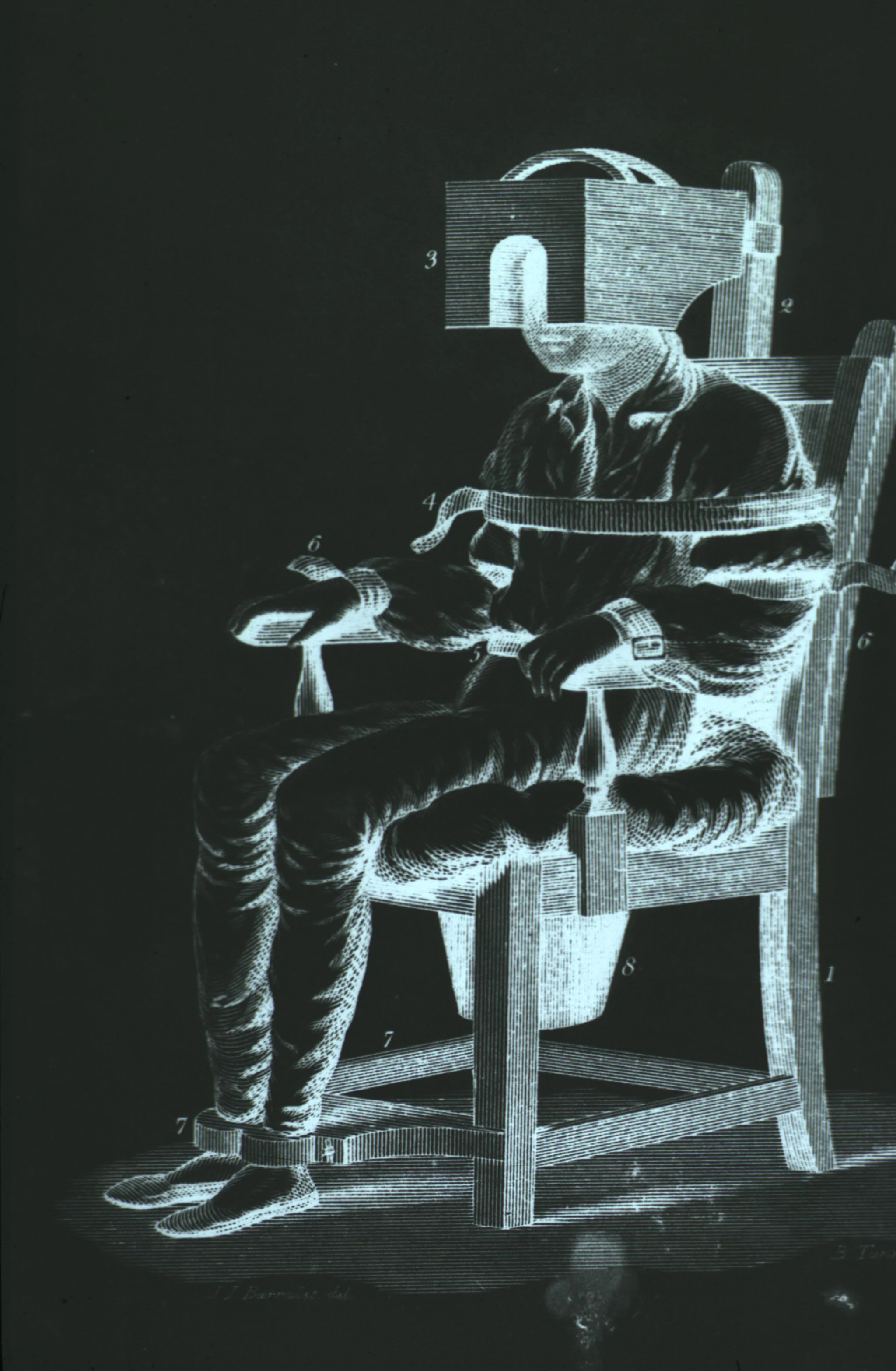

This somatogenic view treated madness as a physical malfunction requiring physical treatments like bloodletting, purging and restraints. Benjamin Rush in America promoted similar methods, even inventing a "tranquilizer chair" to control agitated patients.

Pinel stood on the other side. He argued that mental illness often resulted from psychological stress, social upheaval and environmental factors. His approach, called moral treatment, rejected violence and physical punishment.

Instead, he advocated conversation, purposeful work and humane conditions. This wasn't soft sentiment. Pinel believed reason could reach even those who seemed lost to it, that patients could collaborate in their own recovery if treated with dignity.

Tranquilizing Chair of Benjamin Rush

National Library of Medicine, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Removing chains became political during the Revolution. It was a statement about human rights and the social contract. Even the mad deserved treatment rather than punishment. But uncomfortable questions emerged. Who got to define sanity? What counted as proper treatment?

The debate wasn't settled and may never be. It just moved into new territory, where doctors rather than jailers held the keys.

This was happening as psychiatry emerged as a medical discipline. The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries reframed madness from moral failure or divine punishment into illness. Yet this shift came with its own structures of power. Chains were removed, but institutions remained. Surveillance replaced iron.

Other reformers followed similar paths. Vincenzo Chiarugi in Italy had already removed chains in the 1780s. William Tuke founded the York Retreat in England in 1796, where Quakers treated patients as guests rather than prisoners.

But the movement faced resistance. When researchers discovered brain lesions causing some disorders, physicians criticized Pinel's emphasis on psychology. The somatogenic view surged back, and the tension between physical and psychological explanations for mental illness stretched through the entire nineteenth century without resolution.

The chains fall, but the gaze remains.

This pattern repeats throughout history. Slaves freed into sharecropping. Colonies granted independence while economic dependency persists. Patients unchained but confined to asylums. Each liberation carries the architecture of the previous system forward under a different name.

For nineteenth century audiences, the painting functioned as a progress narrative. It aligned with Enlightenment ideals of reason, science and humanitarian reform, but it also showed that hose ideals do not come without their own challenges.

In hindsight, it reads more ambiguously.

Psychiatric history is not a straight line toward benevolence. It is filled with new forms of confinement, now medicalized rather than overtly violent. It marks the moment madness was allowed back into the human realm under conditions others defined.